After five and a half years, the dead have returned again. On June 24, Death Stranding 2: On the Beach will cause fans to grab a controller, pick up a package, and set out across an apocalyptic wasteland to make new connections between the strands of humanity.

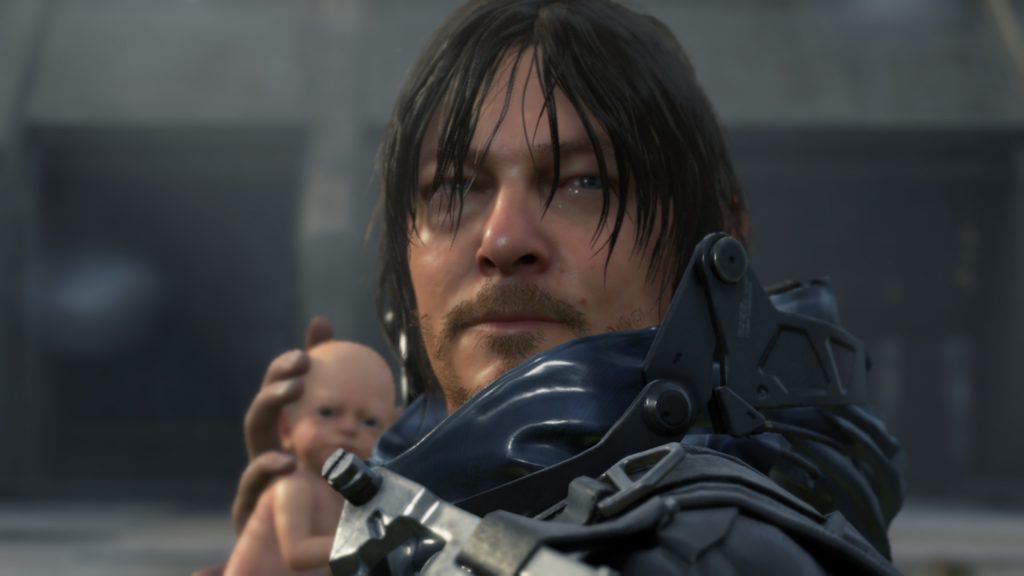

The sequel to 2019’s Death Stranding, On the Beach will see players resume the life of Sam Porter-Bridges, a grief-stricken survivor turned deliveryman who reunited the US during the first game. Between the original and striking visuals, the abstract social commentary, and the promise of something unique from notorious Japanese developer Hideo Kojima, the game attracted huge attention when it released in 2019. It also went on to deter great numbers of players, as the mostly slow-paced logistics game turned out to be not exactly what everyone expected.

With Death Stranding 2 arriving soon, everyone knows what to expect this time around. Ahead of the launch, I went back to the first game to find where this “porter-simulator” delivered, and to seek out the stumbles that Kojima will want to upgrade on this second outing.

A journey through the mind (and the apocalypse)

This also served as an opportunity to complete my playthrough, as after dozens of hours, I still had dozens more to go before finishing the final chapter.

While some books are described as un-put-down-able, Death Stranding is intentionally infinitely-put-down-able. In crafting a slow, meditative game, Kojima Productions made a game that often demands around 40% of a player’s focus.

Online, the biggest fans of the game will often describe enjoying it while listening music or as something they can dip in and out of. Having this level of narrative in a “podcast game” is rare, and doing so with this much budget and prestige is unique. Since I mostly kept my focus on the game, more casual players might be more forgiving of the game’s shortcomings, particularly when it comes to the soundtrack.

Death Stranding makes use of an impressive amount of licensed music, infusing the game’s landscapes with the sombre melodies of Low Roar and the futurisitic sounds of Chvrches. These are timed to play at appropriate points during story missions, bringing a sense of progression and becoming unlocked for players after the mission.

However, once unlocked, the songs can only be played in Sam’s bedroom, with no way to play a song while out on a delivery. With how well chosen the music is, it’s a real shame that this feature wasn’t just slightly more accessible. It feels as though this choice might have been made to keep control of the game’s ambience in the hands of its director, to avoid “spoiling” a mission with an out-of-place track, but keeping the music player inaccessible even after the end of the story feels like an oversight.

From the mountain top, you can see the reveals coming

While he is well known as a storyteller, it is easy to forget that Hideo Kojima is also notorious for his lack of subtlety. After the launch of Death Stranding, social media poked fun at the straightforward naming scheme for the game’s characters. Is the character sensitive to touch? Call her Fragile. Is the character hard to kill? Call him Die-Hardman.

There is a character who, upon first meeting him, insists upon showing the player a scan of his heart. He has a heart condition that makes his heart shaped like a cartoon love-heart, after an accident during his heart surgery caused an entity to leave a heart-shaped mark over his heart-area. Now, he lives by a heart-shaped lake, automatically stopping his heart every 14 minutes for plot reasons. His name is, of course, Heartman.

This eye-roll-inducing storytelling sometimes extends elsewhere. While most songs are effectively chose, the end credits song is so offensively plain in its lyrics, it hugely undercuts the end of the story it follows.

These undercuts continue in some of the story’s reveals. For example, on at least two occasions, Sam is surprised to learn the true nature of a package he is carrying, despite it being clearly shown to the player both times, leaving the emotional “reveal” feeling rather hollow. While trusting players with freedom means that they will occasionally ruin their own story, both of these were easily avoidable.

As a sequel, On the Beach will be building on an already-established universe, and so won’t have to set out the foundations and rules of the world like the first game. However, that also means it has less to reveal about the Death Stranding, and any new reveals will have to come from somewhere new.

Often, sequels spend more time with their characters, and learning the stories of the three new main characters seen in trailers could bring some interesting ideas into the world of Heartman and Fragile. On the other hand, some game sequels tend to launch into big new concepts that don’t really fit with the original, so we have to hope that any expansion to the lore fits in with the first game’s themes of connection, grief, and human relationships.

But, keeping the tone of the first game means keeping some of the whiplash between intricate storytelling and offensively obvious messaging that has become part of a standard Kojima game. At release of the first game, any online jokes not pointed at the game’s naming scheme instead focussed on how a steady supply of Monster Energy drinks somehow survived the apocalypse, thanks to a real-life sponsorship deal. Ultimately, wouldn’t fans would be left disappointed it there weren’t new, immersion-breaking advertising stunts in the sequel?

Death Stranding 2: Getting an upgrade

Part of the reason I gave the game a rest initially was that I believed I had seen most of what it had to offer. While I liked what I had seen, and was happy to have more, it felt as if continuing would require a level of planning and grinding that would counterbalance the fun I had been having up until then. The first thing I learned upon picking it back up again was how wrong I had been, and how clever Death Stranding is with its reward mechanisms.

Despite the big talk of the meaning behind “strand-type games”, the core of Death Stranding relies upon taking packages between a collection of different people, with various conditions and obstacles for each delivery. Every package earns the player “likes”, and at certain thresholds, rewards.

This simple system hides a skilled balancing act. With so many small but meaningful upgrades available at thresholds that always seem within reach, even the most careful planner won’t gain much from trying to work out the most mathematically-optimal route across the map. There is enough information available to build a rough plan, but after a point, the player simply has to pick up their packages and roll with what the game provides.

The trickle of rewards keeps offering surprises, and new ways to make deliveries easier just as you become used to delivering packages the hard way. However, now that Sam Porter-Bridges has already covered this ground, keeping rewards interesting might be more difficult the second time around. Trailers suggest that Death Stranding 2 picks up after Sam abandoned the life he built up in the first game, so narratively, there is good reason for the player to start again from nothing in the sequel. Whether that will be the case, and whether that will be interesting, remains to be seen when the game releases.

The climax

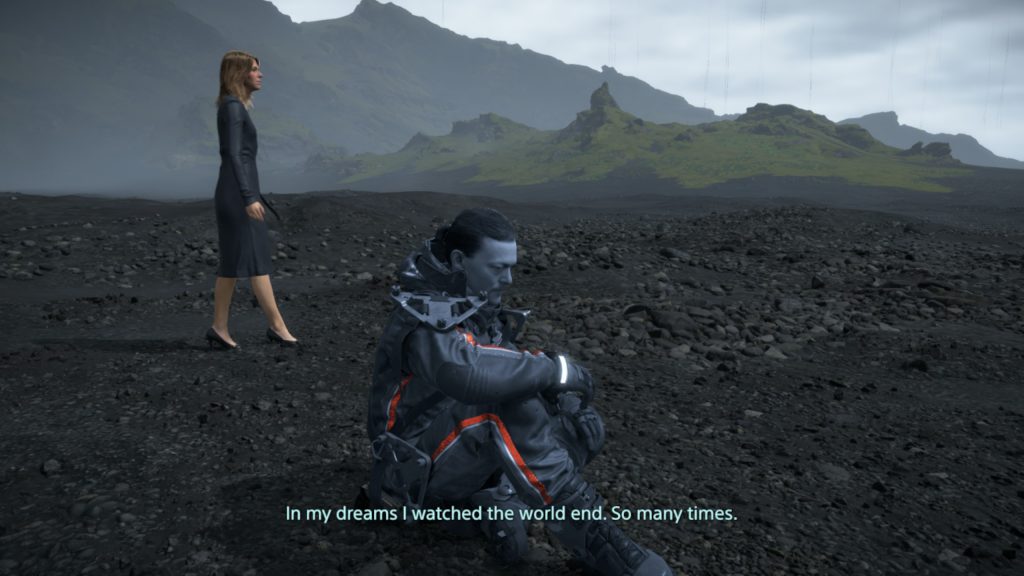

The most obvious flaw in the original game is in its climactic scenes. The main body of the game takes place alone in a serene and natural landscape, encouraging quiet contemplation as Sam crosses a devastated America. Through motion-captured cutscenes, this meditative gameplay slowly builds towards carefully-constructed, high-concept moments of what can only be described as pointless anti-climax, using inadequate mechanics to fight repetitive enemies in boring levels.

These fights throw away everything that makes the makes the main game work so well, and are almost all a slog to get through. Some have interesting level design, but almost all that take place in cities make it clear that Sam’s traversal mechanics were designed for carrying loads through the countryside, not urban combat.

This would not be so important if, to borrow a phrase, the game didn’t insist on itself so much. Fake credits sequences are increasingly common in games, used as a joke in Outer Wilds and to hide the real ending of Dragon’s Dogma. But none of these have an unskippable, drawn-out, one-by-one credits sequence after the apparent climax of the story, followed by another two hours of almost solid cutscenes before the actual end of the game.

While these cutscenes are arranged differently, most of them are not actually telling the player anything new, but are still needed to set-up for the actual ending.

Kojima is legendary within the gaming industry, as one of the few well-known game developers anywhere in the world. He has become synonymous with the idea that gaming is an art, and that games can tell worthwhile stories without sacrificing satisfying gameplay. But if that’s the case, then why is the story such a mess?

Why is this the story?

Death Stranding touches on many themes creeping into the heart of society. Isolation, and the risks and rewards of connection, are the bittersweet juices the player marinades in as they make their deliveries. Relatedly, the effects of the internet, and the endless search for the next dopamine hit, are the foundation of the game’s mechanics. The fact that this game released to PC in 2020, amid Covid lockdowns and societal upheaval, is evidence of a cosmic sense of humour that should be studied for years to come.

But, imagine for a second the game outside of that context, just as Death Stranding 2 will release. Would Death Stranding have hit the same? A game about human connections (or “strands”, as the game insists on calling almost everything), feels slightly less insightful in a world with less time to meditate and more time to, well, socialise.

Addressing these concerns, Death Stranding 2 seems to be taking a darker turn, perhaps dwelling more on the negative aspects of connection, and by extension, the internet. With the trailer asking “Should we have connected?”, Kojima seems to be steering toward looking at the harms of the internet and social media, possibly looking at how it has affected the real world. This would prove equally important today as isolation was in the pandemic, but it would make the sequel a very different game.

In most game franchises, players expect a significant change to game mechanics between instalments. Famously, the Civilisation franchise aims to keep one-third of gameplay the same between releases, upgrading another third, and bringing something totally new to the remainder. However, in a game as story-driven as Death Stranding, mechanics take a backseat to the story, and the new horizons for Sam Porter-Bridges.

If Death Stranding 2 was an almost-identical game with the next chapter of the story, some fans might even be fine with it. The most essential component of the new game will be its story, and how it feels more than how much sense it makes. Still, a new game could stand to be slightly easier to follow, and it could perhaps spend a bit more time telling a satisfying narrative.

But even without these things, plenty of people would be happy to have a reason just to take another lonely journey through the world of Death Stranding, and to be moved by whatever strange feelings Hideo Kojima carefully wove between adverts and meditation. There truly is nothing quite like Death Stranding, but the most certain expectation has to be the unexpected.

Death Stranding 2: On the Beach releases on 23 June on Playstation 5.